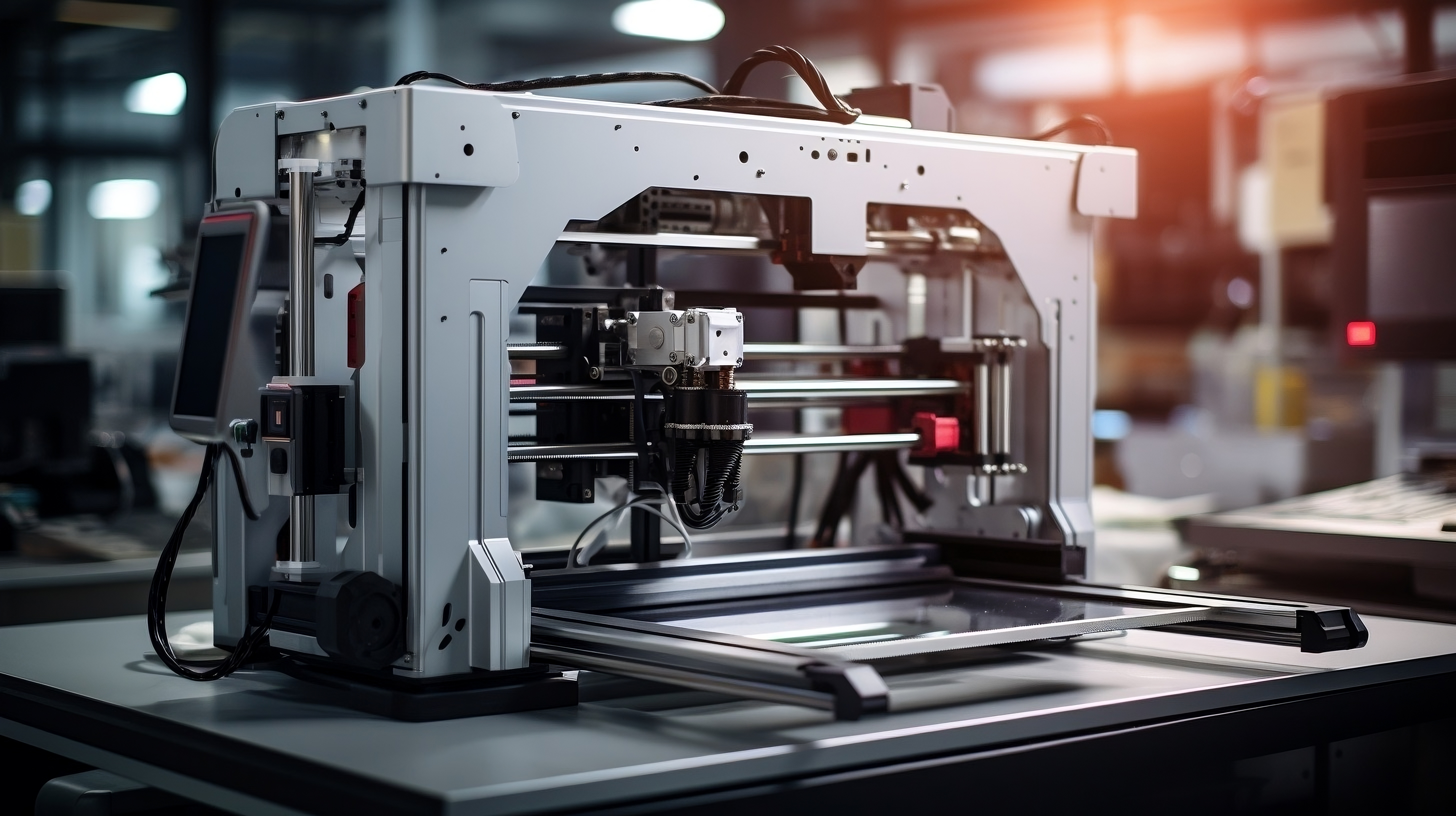

3D printing, or additive manufacturing, is one of the newer forms of manufacturing. As our explainer states, it is a process that constructs a 3D object by using a digital 3D model or CAD asset.

As with many new and developing technologies, there have been more than a few predictions about its implications for various industries.

For manufacturing, and for international trade, one particular prediction caused waves several years ago.

The prognosis

In 2017, Dutch bank ING predicted that 50% of manufactured goods could be 3D printed within the subsequent two decades.

“It functions as a wake-up call for our clients because this can certainly influence almost all manufacturing sectors. There is a possibility that this could evolve quickly,” Raoul Leering, senior macro economist at ING, told Global Trade Review.

If this happened, ING estimated that almost a quarter of global trade would be wiped out by 2060, possibly even earlier if investment in printing technology was increased.

Aerospace, consumer electronics and medical devices were some of the industries expected to suffer from increased additive manufacturing, as goods such as hearing aids and parts for planes could be 'printed'.

So what happened? Are we a quarter of the way to seeing trade drastically diminished? Will we see trade flows plummet?

The update

In 2021, ING updated its predictions, to reflect the past four years since the initial piece of research.

“3D printing is still in its infancy. For now, it has very little effect on cross-border trade,” said Leering.

In 2020, the demand for 3D printing technology fell, with those companies that used it reporting a revenue fall of 7.5%. Their average annual revenue growth was 25.2% in the three previous years.

As with a many things, Covid was the main culprit.

Leering, a former economist at the Dutch finance ministry, predicted that this would change once the technology advanced further.

‘Winners and losers’

The question remains: will additive manufacturing hit international trade as hard as predicted?

“I highly doubt it,” said Joshua Dugdale, head of technology & skills at the Manufacturing Technologies Association.

“I can see the logic, because suddenly your whole supply chain can be digital and you can manufacture at the point of need, but you need a certain level of skills to be able to run machines in certain places.”

Michael Petch, editor-in-chief at 3D Printing Industry, a specialist news site for the additive manufacturing industry, largely agreed with the sentiment that global trade would not be impacted as heavily as suggested.

“I question whether this would ever be the case,” he said of ING’s prediction, noting that there were entire industries that additive manufacturing would not be appropriate for.

“I can’t picture it myself, but there are always new technologies on the horizon.”

Petch said that goods like commodities and fuels and mining products, where 3D printing has minimal application, would likely mean that certain aspects of global trade would never be replaced. There are also entire industries that, as it stands, would be completely inappropriate for use in 3D printing.

“I’ve seen some pretty bold stuff that borders on the realms of science fiction—claims of 3D printing producing chemicals and things like that, but I’m not sure about that.”

Skills and innovation

3D printing is not an easy technology to adopt en masse. To really hit trade would take more than a few extra printing machines in the back office. Dugdale explained:

“You’re not going to have manufacturing capability everywhere across the world to the same level, so there is still going to be an element of trade.”

Local supply chains could still be impacted, however, by on-site printing services for certain items.

He gave the example of how additive manufacturing is impacting supply chains in North America:

“In Canada, there's a company called Polyunity, and they've set up these little 3D printing farms in hospitals there, and are the manufacturing all the plastic, consumable parts on site.

“They used to spend $90 every time they broke a bed bumper, buying a new one. And you have to buy 1,000 at a time and store and transport them.

“So suddenly, the hospital can make components on site. Now, if you break one, someone goes to a computer terminal and clicks print. Two hours later, it’s basically on the desk and they can fit it to the bed.”

While certain nations and regions are trying to build up their additive manufacturing capability, most of it is focused in one place.

Dugdale says that as of right now, the US is far and away the single largest source of additive manufacturing.

Geopolitics

“They’ve had this massive backing from the government,” he said of US president Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, which provided over USD $1bn to help companies adopt additive manufacturing techniques.

There’s nothing of that scope being done in the EU, Asia or the UK, according to Dugdale and his European counterparts. Governments without the US’ deep pockets are having to focus on a few select industries, and for many, they’ve picked alternatives like artificial intelligence.

A concentration of additive printing in one region would likely mean that most countries are still expecting to move goods across borders.

Trade may shift another way, according to Petch, who cites the examples of companies producing printed goods in places that are not typical manufacturing hubs, like central London.

Not suitable for some

Another issue is the process of using printers, that makes it unsuitable for producing certain types of goods.

Additive manufacturing takes place by adding materials layer-by-layer to create a shape, rather than shaving something off an existing object. This process is inherently slow.

Printing machines are slow and can take a long time to ‘build’ an object, so more traditional machines that can process thousands of smaller, cheaper items will still win out. Mass-methods of production are unlikely to be replaced, so countries like China, Vietnam and other nations that rely on this for their manufacturing base are unlikely to see it threatened by additive manufacturing.

Other materials, like wood, cannot yet be properly incorporated into the additive process, since any materials need to essentially be melted and reformed in layers to manufacture a part.

Additive manufacturing is also suitable for materials which solidify without heat such as concrete; the most suitable ones are metals and polymers (plastics).

Winners…

While it looks likely to be more of a reform than a revolution, additive manufacturing should still have some impact on international trade.

Experts have said that winners and losers are likely with any new technology, and the additive manufacturing industry itself exports, providing new opportunities.

It is a service that can be exported and imported, while firms now have the ability to ship both the machines and the materials abroad.

Raw materials used in additive printing, such as wires and powders, are beginning to be shipped in place of bars and plates.

Specialist printers have said that finished parts and products made with additive manufacturing will always be shipped around. It just isn’t possible for everyone to manufacture the parts in every location or country, according to many in the industry.

…and losers

On the other hand, others may be negatively impacted, particularly those in smaller industries producing custom items.

“When additive manufacturing was first adopted, some industries just got wiped out,” said Petch.

“Hearing aid businesses and other smaller healthcare sectors had to adopt the technology or go out of business.”

With several, smaller industries, 3D printing was the final challenge for many. It was simpler and easier to produce custom, one-off items. They had to change their habits or face extinction.

Yet, for most manufacturers today, Petch says that it represents an opportunity rather than a challenge.

“People have to open up the reality a bit in relation to integration,” says Petch, adding that he sees it becoming more of a “complementary technology”.

Screwdrivers and builders

Additive manufacturing being ‘complementary’ is certainly a theme throughout multiple interviews. One expert gave the following analogy:

“When electric screwdrivers were introduced, people thought, ‘what's the impact on the building trade? Well, we can build things faster.’ Did that mean we're not going to need as many carpenters or builders? Well, no. In fact, they can be quite difficult to find nowadays – it’s all down to demand and supply and rates of growth”

“So, you can see that when something new comes, it’s not necessarily a negative impact there. It can also enhance and compliment how we manufacture.”

This is a similar theme with other new and as-yet-unexplored technologies. Will artificial intelligence replace doctors, or will it just help speed up diagnosis and free up medical professionals to focus on other areas?

In the same vein, would additive manufacturing just mean that a good is printed in one location and shipped to another to be finished or slightly modified?

Many different industries are looking to integrate additive processes into their existing supply chain, both as matters of survival and of efficiency.

Defence, space and electronics

For the advanced and specific manufacturing processes, additive methods can play a crucial part.

Recently, defence manufacturers HII and General Dynamics Electric Boat announced they would use 3D printing to help produce parts of nuclear-powered submarines.

Defence is one of the areas that Petch has seen a particular interest in for the wider industry, citing the example of an Israeli company working to produce goods in Germany for use in Ukraine’s war effort against Russia.

Top-end machines can be used to produce goods that are very complicated and safety-critical for use in highly technical industries like aerospace.

The cost of this, however, can be a barrier for entry for some, as it requires extensive investment and training.

So what happened to the future?

The conclusion of most of the experts is that additive manufacturing won’t wipe out trade in the manner that was at one point estimated by ING and others.

Dugdale, being a representative of a manufacturing association that represents additive manufacturers, says that there was an “element of truth” in the original study, but it was “overstated”.

Petch, a long-time journalist working in the industry, believes that 3D printing will still have a big role in the future of manufacturing.

“It’s really down to the 3D printing industry to show its value,” says Petch, noting the myriad of possible opportunities that additive manufacturing has brought to various industries.

Even in ING’s second report, it described the difficulty of predicting the “future share of 3D printed goods and services in manufacturing globally.”

Predictions made several years before, based on emerging technology, will always be subject to change—Google Glass once looked to be part of everyday life.

As it stands, the consensus view from experts is that additive manufacturing will be integrated into international trade.

With geopolitics turning turbulent export controls exploding, new challenges are on the horizon. Evolving technologies like beam shaping, however, could completely change the 3D printing and its prospects. To paraphrase one expert, today’s science fiction is tomorrow’s reality.