At the end of 2021, the economy looked on course for a period of economic recovery during 2022. It was a relief after two challenging years of pandemic. But as 2022 draws to a close, the prospects for the UK economy look very different from that initial view.

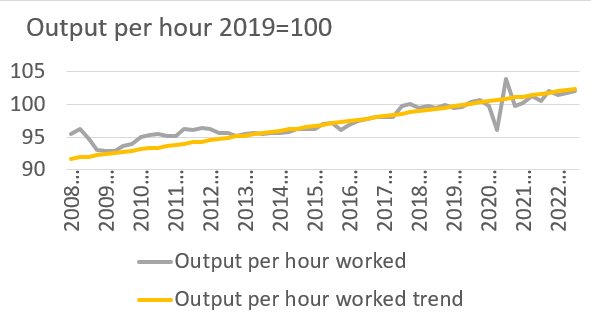

One way of looking at this is to compare the Bank of England (BoE) forecasts for 2022, 2023 and 2024 made in November 2021 with those it made in November this year. These forecasts cover economic growth, consumer price inflation (CPI), the main bank interest rate and unemployment. The comparison offers a sobering and comprehensive summary of the change in economic prospects and conditions during 2022.

In its November 2021 inflation report, the BoE, via the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), forecast that economic growth would be 5.2% in 2022 then slow down but remain positive for each of the following years.

All its predictions have proved wrong. Economic growth has turned out to be more like 4% this year, almost a percentage point below what it expected last year.

Fig 1: Bank of England forecasts for 2022 have proved to be wrong

Instead of a few years of uninterrupted growth, the BoE’s forecast is now for recession in 2023 and 2024. Moreover, the economy will only surpass its 2019 Q4 GDP peak in 2025. In its November 2021 report, the Bank expected the economy to reach that 2019 Q4 peak by Q2 2022. CPI has peaked at over 11%, compared with a forecast 3.7%.

The bank rate has hit 3.5% and will go higher than the Bank forecast in November 2021. Projections of interest rates of 1% in 2022, 2023 and 2024 now look very naive. The unemployment rate is the only variable close to the MPC’s 2021 forecast. So, what went so badly wrong with these forecasts?

Events have derailed forecasts

The Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24th primarily accounts for this deterioration, derailing all predictions everywhere, with the UK no exception. That said, we must distinguish oil-exporting from oil-importing countries.

Only some have done badly because of rising oil prices. Predominantly oil-exporting countries have done well from this crisis, at least those who have not been so impacted by food price inflation. On one estimate, the rise in oil and gas prices has transferred $1.33trn of wealth from energy-importing countries to exporting ones.

The UK economy had only just begun to recover from the supply-side shocks stemming from pandemic shut downs. It was, therefore, more susceptible to shocks than the MPC thought. It was lulled into a false sense of security because some semblances of normality started to appear.

But it would also be disingenuous to suggest that all the UK’s problems result solely from this. Several other factors have played a role in making the UK particularly vulnerable to the shock of the invasion of Ukraine.

One was that domestic monetary policy had been too loose for too long, as evidenced by accelerating growth in the stock of money held by the UK private sector. Inflation, unfortunately, was always likely to result if the UK experienced a shock, which it has. Growth was similarly at risk, with the rise in inflation eroding real incomes further and lowering living standards. Further reduction in disposable incomes is caused by the rise in the Bank rate, which increases mortgage payments and other borrowing costs, leaving less for households to spend.

Money supply was also expanding too quickly

The $150bn of quantitative easing (QE) by the BoE - buying bonds from the private sector - is now seen as a mistake. With hindsight, it led to too fast an increase in the broad measure of money, M4.

The latter’s annual growth rate surged to 16% during 2020, presaging price inflation in 2022. Without the war in Ukraine, UK CPI may not have risen to double digits, but it would have been at least twice the BOE’s target rate of 2%.

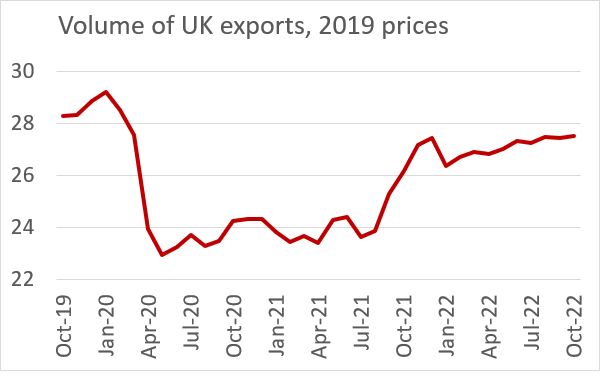

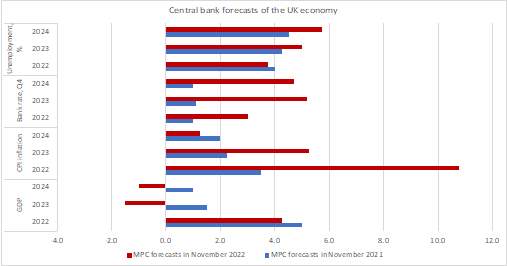

But the UK faced other headwinds as the economy entered 2022, some from Brexit and domestic policy choices made by governments and voters since 2007/8. These have led to supply-side shocks for the UK in terms of productivity growth (which has been poor, see chart 2 below), employment (which is still below 2019 levels) and export growth (with exports lower than 2019 levels, see chart 3).

Fig 2: UK productivity has suffered since 2008

Fig 3: UK exports have yet to regain 2019 levels

Measured by output per hour, UK productivity is the lowest of the G7 economies, and the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) continues to estimate that the hit from Brexit is greater than the impact of the pandemic.

Moreover, there are issues with the economy’s supply side that stem from the over-centralisation of decision-making, a lack of flexibility in planning for housing, and lack of spending on infrastructure. Even though public investment in real terms is lower by 20% since the 2010 financial crisis, in the November financial statement by Jeremy Hunt, it was again cut or frozen.

Political turmoil has not helped the economy.

But the UK also faced unprecedented political turmoil. It has had three prime ministers, three chancellors of the exchequer and various changes in senior ministerial posts in the last year. It has had five fiscal events in 2022. The first was the March budget by now prime minister Rishi Sunak, followed by another one three weeks later to rectify omissions in the first one. Third, the September 23rd mini budget by Kwasi Kwarteng. Fourth the undoing of that by the newly appointed Jeremy Hunt. And fifth, the actual Autumn Statement in November, in which Hunt laid out a new set of plans for the UK economy over the next few years.

Therefore, political, and monetary instability has played out alongside the economic challenges in the aftermath of the pandemic, the UK’s departure from the EU and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The surprise would have been if these events had not had implications for the real economy.

For instance, the series of strikes in the public sector that the UK is facing is partly a consequence of policies enacted because of the global financial crisis in 2008/9 by then chancellor, George Osbourne. Public sector pay has grown more slowly than in the private sector in every year since 2010, except for during the pandemic.

The current gap between private and public sector pay is the widest it's been in any period since. The consequence is falling living standards for those who work in the public sector, including nurses and ambulance drivers.

It is also the culmination of years of underinvesting in low-cost accommodation for those with average salaries in the UK. Since 2008, pay adjusted for CPI inflation has stagnated, yet house prices rose by 53% in the last decade and rents were up by about 35%. The only real surprise about some of the pay disputes we are experiencing this winter is that they haven’t happened sooner.

But all recessions end

So, there is a context to the turmoil in the economic and political sphere now affecting society. The challenge is clear: how to pay for publicly funded services at the standard now expected in the UK. This has to be worked out politically.

In the economic sphere, the challenge and opportunity are how to resolve the blockages that result in persistent low productivity and weak growth. And these changes must happen in the context of reduced access to a trading bloc that still accounts for around 45% of UK exports.

Let's hope the MPC’s forecasts are wrong this year as well, particularly its projection that the current recession will persist into 2024. We also need to hold on to the fact that not every part of the economy will contract and that some sectors will grow. There are still opportunities. We’ll know the worst of the crisis is over when inflation falls – as it surely will - and interest rates are cut, likely sharply.

Professor Trevor Williams is a former chief economist at Lloyds Bank, a visiting professor at the University of Derby and co-founder of FXGuard.