The UK trade deficit - Photograph: ONS

In the year since the UK voted to leave the EU last summer, many have predicted that the consequent weakening of pound sterling would in the short term boost the UK’s exports. Many have also called the Brexit vote an opportunity for the UK to better embrace trade with the rest of the world, with project ‘Global Britain’ looking to increase exports to non-EU countries.

Today’s figures released by the Office for National Statistics do plenty to undermine both of these predictions, with the trade deficit growing, exports falling, and the UK’s reliance on trade with its EU partners growing.

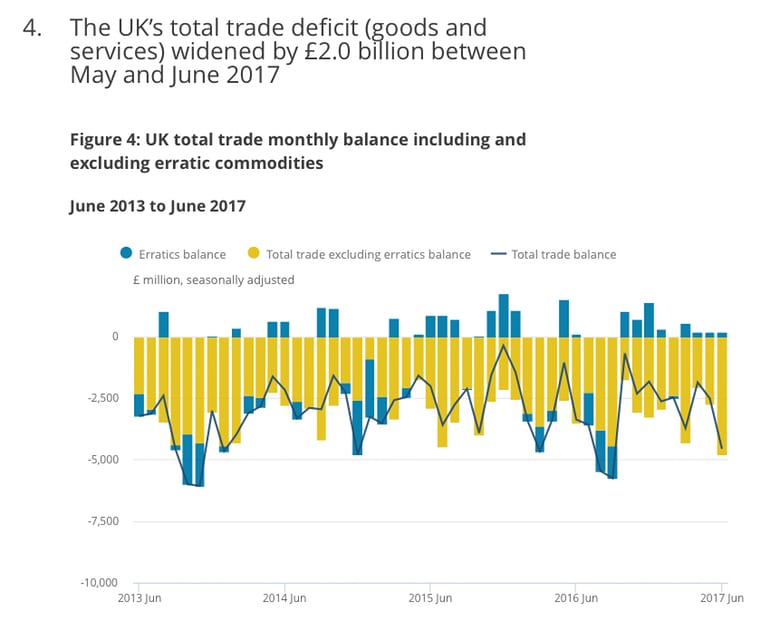

The trade in goods deficit widened to a 9-month high in June to £12.7bn from £11.3bn in May, with imports up 1.6% and exports down 2.8%.

With the pound 13% lower against the dollar and 15% down against the euro in comparison to the day of the referendum, it had been predicted that the UK would be less able to afford to import goods from strengthening currency markets, while its own goods would become more affordable to international customers. But with it becoming more and more apparent that exporting itself incurs supply chain costs – including, in many cases, imported parts and machinery – this assessment is beginning to look wide off the mark.

What will certainly concern the UK government are the figures showing that exports to non-EU partners are in fact decreasing while exports to EU partners are increasing.

This could mean a few things.

It could mean that UK businesses are trying to enjoy the free trading environment in the EU while they can, while preparing to grow their exports elsewhere at a later stage.

It could also show that trade with the rest of the world remains more difficult than with the EU because the free trading climate we have with the EU isn’t there in these markets. Though this is something the government will look to improve once it is able to agree free trade deals with markets around the world as an independent state outside of the EU, this is an issue that will take a lot of time to resolve.

In the meantime, the UK will likely have to trade using WTO rules.

In this medium term, being out of the EU with a worse trade deal (or no deal) with its European partners, and with no deals agreed yet with non-EU partners, the UK could be faced its least barrier-free trading climate in decades.

This trading climate, if these latest figures are to be believed, could be interpreted as one that UK companies are finding harder to deal with rather than easier.